By Chris McGrath

His father always told him how his were “the first footsteps in the snow.” Long days, hard work, crepe paper and cork factories: a classic immigrant tale of New York. But there was an intellectual legacy, too. The man spoke 13 languages. Thirteen! Now Peter Brant is in turn reiterating to the next generation-and he has no fewer than nine children-that wealth alone is no guarantee of fulfilment, that it must be sustained by engagement with the challenges and beauty of a world widened by privilege.

“I had a father I was very close to, and not a day goes by where I don't think about him,” Brant says. “He was a great man. And he always told me that what you have between your ears is all you've got. And never to count on anything other than that, because it will lead to misfortune. And I try to tell the same thing to my kids.”

Sure enough, while his twin passions plainly require uncommon funds, both his art collection and his racing stable measure resources of quite another kind, if equally rare. For both answer the same kind of inner need.

Nor is it merely a question of a Thoroughbred's aesthetic appeal-so familiar, after all, that Lord Howard de Walden even had his apricot silks chosen by the painter Augustus John to complement the green backdrop of a racecourse.

There is a seamless integrity between Brant, the owner of racehorses, and Brant, the collector of modern art; between his curiosity about the mysteries of the creative process, and the breeding of an animal that so perfectly combines form and function. His stable represents a parallel process of collection and curation, in the hope of turning up a masterpiece.

Extending the analogy, we might speak of “early Brant” and “late Brant” respectively to describe the likes of champion Gulch, during his first spell in the sport, or the filly who sealed his comeback from a long exile at the Breeders' Cup earlier this month. The success of Sistercharlie (Ire) (Myboycharlie {Ire})–exported from France last year–in the Filly & Mare Turf represented a first racetrack headline on the scale of those Brant has been making at the sales, either side of the Atlantic, since returning to the fray in 2016 (notably at the Wildenstein dispersal).

“It meant a lot,” Brant admits. “It has been such a pleasure to be around a great horse, just to watch her being trained over the last year or so. Especially after she got sick on us when she came over and ran in the Belmont Oaks, a case of pneumonia that was nip-and-tuck for a while. Gary Priest [veterinarian] did a great job with her, as they did in the [Cornell] Ruffian [Equine Clinic] at Belmont Park, where she was for about 10 days. Slowly, we got her back into training, and Chad [Brown, trainer] did a great job taking care of her.”

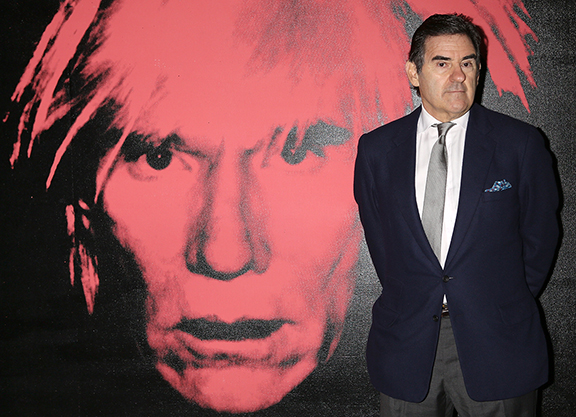

The first piece of art Brant ever bought was by a young guy named Warhol. With the same, unerring knack, he picked out the emerging Brown to assist his return to the sport, after an absence since the early 1990s to address sundry business and personal distractions.

“I was very fortunate to have been in this for 20 years, breeding and raising horses, before getting back into it as an older, more experienced person,” Brant reflects. “And I think I tried to use those past lessons to maybe not do a few things I'd done before-even though we'd been very successful. No matter how successful you are, you make mistakes. So I tried not to follow the exact same plan. I found big changes in the way horses were being trained, and in the veterinary science, in how active stallions can be. And all those things change the fundamentals.

“When I decided to come back, I hadn't yet met Chad. But I tried to do as much research as I could. I think Chad is just a very focused guy. He's passionate about what he does, takes it very seriously, spends most of his time thinking about his horses. He's a quintessential achiever, he's intelligent, he concentrates on the detail. And-a very good thing-he knows when to stop on a horse. The other great thing about Chad is he thinks about races way in advance. If he doesn't make it, he doesn't make it, but at least you know the direction you want to head; at least he's thinking about what kind of race is going to suit this horse best, rather than waiting for the horse to be right, and then saying okay, now let's look for a race.”

If finding a trainer is akin to backing an artist, then that makes each racehorse like a painting. Because Brant explains that genius can be as hard to explain, relative to an artist's personality, as the brilliance of a racehorse with modest genes.

“Sometimes art does reflect on the artist's character, but sometimes it doesn't,” he says. “Because expression comes from within. You can read about artists, and talk to them, and obviously you can't really do that with horses. But if you're looking at collecting-putting together a group of horses, or putting together a group of paintings-then there are certain principles that are similar. For instance, usually recognizing the talent beforehand is much more difficult than after it has performed for a number of seasons. Trying to pick a younger artist today who's going to flourish in the future is very difficult, it's like picking a weanling you hope can run in Group 1 races.”

Both instincts were honed in boyhood. The actual horsemanship admittedly did not come until later, when building his own polo and racing operations. First of all there was betting, and the kind of hard-knocking horses you could trust with your pocketmoney as a kid in Queens.

“My heroes, besides Duke Snider and Mickey Mantle, were Kelso and Carry Back,” Brant recalls. “Great handicap horses, great weight-carriers. Horses you saw every year. When you're a kid, four years is a long time. So you never forget those horses. And I used to spend my summers at camp in Saratoga. It seemed like I was always either sneaking out of school or camp to go see the horses. We'd go to the racetrack, ask some elderly person to take us in. As soon as you got in, you just walked off.”

At the same time, Brant was getting an apprenticeship in classical art from his father-starting at that local jewel, the Frick, and proceeding to global benchmarks at the Prado and the Louvre. But his mentor in the avant-garde was the Swiss dealer Bruno Bischofberger, then still only in his twenties himself.

“And he would say to me: 'Look, you're living in New York where all the great art is being done now',” recalls Brant. “'Forget the Impressionists, the Cubists. Spend time with the artists living and working in your own town.' And it was a special time in New York. You had Warhol, and Jasper Johns, and Lichtenstein. Rauschenberg. Cy Twombly. So I was very lucky to be living and working there.

“It's like if you're around the racetrack, you see different things than somewhere else. It's living a life dedicated to the love of something. The aesthetics of life are very important to me, and that's kind of where I gravitated, somehow or other. And in a way, horses are that too.”

Warhol soon became curious to meet this young man who was collecting his art and they soon became close friends, collaborating in various projects including films and magazines. But Brant was meanwhile proving equally precocious in his equine investment-and here, too, he learned to think outside conventional boundaries.

“I don't follow axioms like if the horse runs on the turf, their get will not run in the dirt,” he says. “I try to look at the racing style. I do believe a horse is a stayer, or a sprinter, and that the best kind of blood are milers-that's where you're getting the least that can go wrong. But there are exceptions to everything.

“I was very fortunate to breed a Kentucky Derby winner [Thunder Gulch] from English staying stock. I brought Shoot A Line over, she'd been second in the Gold Cup at Ascot, she'd won two Oaks. I bred her to Storm Bird, she had Line Of Thunder that Luca Cumani trained for me, and he won a nice stake with her. We shipped her over for David Whiteley to train as a 4-year-old and then bred her to Gulch.”

The paradox, of course, is that the rule-breakers eventually reset the norm. Work disparaged by conservatives today becomes the priceless must-haves of tomorrow.

“I never bought anything because I thought it would be worth a profit,” Brant insists. “You believe in an artist, you accumulate the work. If the artist is still alive, you hope they continue in the same direction, don't get sidetracked. But it's important art is something you really live.

“Because art really is the first turn to change. The artists show it to us before we see it on television, or in advertising or design. Great art becomes socialized. It's radical when it's first created. That's why most people don't really like contemporary, edgy art. But what's beautiful today is not what was beautiful 20 years ago. Twenty years ago, if you looked at a silkscreen portrait of Marilyn Monroe, that's not art. Today, it looks like a Madonna.”

Again, moreover, he sees parallels in racing. “It all evolves,” he reasons. “Most great artists are students or apprentices of other artists. And who are all these great trainers? They all apprenticed for other great trainers: Bobby Frankel, Wayne Lukas. That's such an important part of our culture: to learn from somebody you respect, to soak in that knowledge and really watch carefully what they're doing, and ask yourself why they're doing it.”

One of the principal challenges to Brant during his absence from racing was itself a result of radical change in social habits, newsprint no longer being the indispensable medium it was when White Birch Paper started. He reckons there were then 34 rival manufacturers; and that now, east of the Mississippi, he faces only two.

“It's a much more consolidated industry, with much less capacity,” he says. “It was very tough for a while, as consumption went down, but it's been very good recently. But you know, I think the country is figuring out that feeding news to the public is a serious responsibility; to provide the correct information, from all different sides, edited so it's not totally out of whack. That's what made our democracy, and that's what will continue it.”

That observation makes it impossible not to ask Brant about his boyhood friendship with the man whose excoriation of traditional media has become a trademark of his rise to the highest office in the land.

“I can only say that my experience with him, as a boy, was that he truly was a very good guy,” Brant says of Donald Trump. “I was friends with him, from five till 13, best friends really, and saw no signs of any kind of bigotry or anything like that, that people accuse him of today. We were two guys who grew up together, and we parted because his father took him into a military academy. Why, I don't know. He never really got into any trouble.”

The two men have not spoken in recent times and Brant's politics, as you might expect of a man of the arts, are of a rather different hue. Regardless of where you stand on the spectrum, however, Brant feels that all sides should be dismayed to see old school journalism–keeping government accountable and the citizenry informed–chased out by the kind of bite-sized trashtalk voters tend to consume today.

“I think that what's happened with the internet, and more sources of news, is that some of them very profound–and some of them are not,” he says. “The ability to express one's opinion is more spread out. Uneducated presentations are being made, all these theories about what's happening. It's not good if people stop reading the newspaper and just go onto the easiest thing they can find. We should all read a variety of newspapers, online or in print, as part of our life to educate ourselves. But I wouldn't be in horse racing if I wasn't an optimist! And I am an optimist, no question about that.”

Brant stresses how no nation better illustrates the cultural energy of the melting pot. Think of Warhol, son of a Pittsburgh coal miner, whose antecedents were (aptly enough) Bohemian. In fact, think of Brant himself–this charismatic, craggy septuagenarian, a living link to the brilliance and industry and dynamism imported from Europe by his father: a man of Spanish roots, raised on the borders of Rumania and Bulgaria, educated in Germany.

“That's why so many people born in Brooklyn have become great,” Brant says with enthusiasm. “Why it has produced so many creative geniuses. They were street-smart, their neighborhoods were full of diversity. It's what our country is all about. Why did all the artists wind up in New York? Basically because they were expelled from Europe–whether because they were Armenian or Jewish or Catholic or homosexual. So that diversity gifted this country.”

His father used to tell Brant that the most important thing a human being must have, and understand, is hunger; that otherwise “the passion is diluted.” And if the next generation of the family has been spared a literal hunger, to the extent that its charitable foundations instead keep the wolf from the door of contemporary artists, the passion in Brant is transparently undiminished.

His comeback should leave the industry feeling doubly blessed: not only in the scale of his renewed investment, but also in the sheer caliber of the investor. For here is a man who connects with our trivial walk of sporting life much as he does with human endeavor in a more profound register, placing the puzzles of equine pedigree and performance alongside those of art, film, politics, philanthropy.

Brant's father went into business with his cousin, Joe Allen's father–and it was Allen, the breeder of War Front, who helped lure his kinsman back onto the Turf. But in a sense, Brant never left, in that he has never ceased to ponder the margin between luck and judgement, between instinct and technique. Even as he retreated, remember, he became the only man to have bred both the mare and stallion he put together to breed a Kentucky Derby winner.

“As a breeder, you might say I need a little bit of this in the pedigree, but then find you're getting something else,” he says. “It's very difficult to quantify. People try to quantify it by nicks, or conformation, or racing style. But because you're dealing with such a large gene pool, for so many generations, you never know where the great sire, mare, racehorse is going to come from.

“We all think we can narrow it down. We look at the percentages of stakes horses a sire produces. But it's really always in the bottom 10%. It's not like you're dealing with a 40% number, and a 2% number. A lot of it is just how they accept training, how they recover from adversity. How they're raised. Living conditions. How they learn to be competitive.

“Horses teach you to be humble. Every day. And we can all do with more of that. It's a very difficult game to play. Nobody is ever going to control their own fortunes. And basically that's the romance of racing or breeding a horse. That's what makes it great.”

Not a subscriber? Click here to sign up for the daily PDF or alerts.